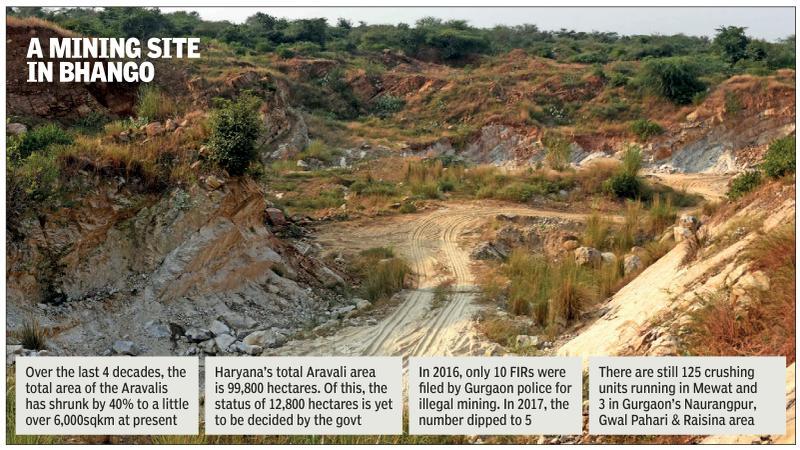

But the pleasantness is short-lived. As one gets closer to the hills, the scars begin to show, then the gashes. At Bhango, around 35km from Gurugram on the border with Rajasthan’s Alwar, entire hills have been defaced. Giant hollows have appeared on the rocky mass, altering the pyramidal shapes of several hills, an outcome of many decades of stone mining that has ground on despite bans, rules and court orders.

These are the same ranges which, another few hours’ drive down the same road, have started disappearing in Rajasthan, where the axe of mining has fallen so regularly and brutally that entire hills have simply been wiped off the landscape. In their place have appeared dusty barren gaps that let the desert wind blow freely towards Delhi, compounding the capital’s problems with pollution.

Mining is banned in the Aravalis in Gurugram, Faridabad and Mewat (now Nuh) since 2002, through a Supreme Court order. But it never stopped in Bhango, which isn’t too far from the Nuh-Alwar border on the Haryana side. It was largely driven by the mining apparatus that operated in Rajasthan after the crackdown in Haryana in 2002.

The damage this has wrought to the ranges in Nuh is glaring. In place of rocky pathways that one expects to see between two hills is a wide dirt track with criss-crossing tyre marks of heavy trucks. These continue deep into the ranges, for around 3km, towards Tauru town. Just off the highway, cars cannot negotiate this terrain, but large trucks regularly do after dark, taking out tonnes of stones every week, say villagers.

A couple of giant craters — each 2-3 feet deep and 8 feet across — as “check posts”. “Cars or jeeps used by enforcement officials get stuck in these, so they don’t go any further,” says a local resident. The soil around the craters appeared to have been freshly dug, indicating they had been dug and enlarged to prevent officials from venturing ahead. “Illegal mining has been going on here. We keep hearing the dynamite blasts and movement of vehicles after sunset, once or twice every week. But we don’t venture out, fearing for our safety,” he added.

TOI photos by Indranil Das

Years of abuse have created deep cavities in the terrain, up to 200-300m at certain stretches, which have turned into seasonal lakes. But even those will vanish in the coming years if illegal mining is not curbed completely. At the nearby Raisina hills in Chehalka and Rithoj villages, the damage to the ranges is similar. It gets worse in Rithath village, located along the Rajasthan border.

The Supreme Court’s central empowered committee said in its report last week that 31 of 128 hills in the Aravali region of Rajasthan were gone forever. How much longer before the same starts happening to the ranges in Haryana? At Bhango, Chehelka and Rithoj, villagers say the clock has anyway started ticking, and the landscape today has lost large portions of hills they had seen in their youths.

Activists have said banning illegal mining in Gurugram, Faridabad and Mewat won’t be sufficient if stone crushing units are allowed to continue in the vicinity. Miners don’t take stones quarried in Haryana across the border, but straight to local crushers, camouflaged under a thick layer of sand. There are 125 stone crushing units in Mewat and three in Gurugram’s Sohna subdivision. It is estimated that currently, 4-5 trucks carrying illegally mined stones arrive at these units every week.

“Two years ago, we wrote to the state government that we need to ban the crushing units along Pali on Gurugram-Faridabad road along with the mining ban. So long as these units exist, violators will have a readily available option to disguise their illegal activity. Our experience shows illegal stone mining could be curbed only in areas where crushers too were shut down,” said Jitender Bhadana, an environmentalist.

Illegal mining isn’t the only problem, though — stones from the Aravalis are in high demand locally to build houses and boundary walls. Sources said the Central Empowered Committee inspected the hills in south Haryana in July this year and listed stone quarrying by villagers for personal use as one of the factors behind the damage to the hills.

“While accompanying the CEC team, we noticed piles of stones outside homes, for use in construction. But officials dismissed it, saying it was for personal consumption and not for commercial use. But the fact remains the hills are being damaged and stones are being used,” said Ramesh Arya, who filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court against illegal mining in Haryana and Rajasthan.

Rajendra Prasad, mining officer for Gurugram and Mewat, admitted theft of stones in Mewat but said there was no illegal mining in the Gurgaon area. “Although there is some theft of stones in Mewat, even that is not illegal mining. Our survey shows there is a 3% theft of stones in Mewat in comparison to what it was till 2002. This theft is by residents who use the material for building houses there. We cannot completely curb this as local sourcing is difficult to stop,” he said.

from Times of India https://ift.tt/2SpWNtR